Climate change: perceptions and experiences

Although nearly 60% of Africans are aware of climate change, some of the continent’s most influential countries lag behind in widespread awareness

Across the continent, African citizens have begun to witness the consequences of climate change, driven by human industrialisation and the pursuit of economic growth. Climate change is a gradual process of average climate modification, which is what has made it difficult to track or detect based only on human personal experience. Every day we experience variations in temperature according to the time of day or season of the year. This makes it challenging for ordinary citizens to really comprehend the risks associated with a global average temperature change of 1.5 or 20C.

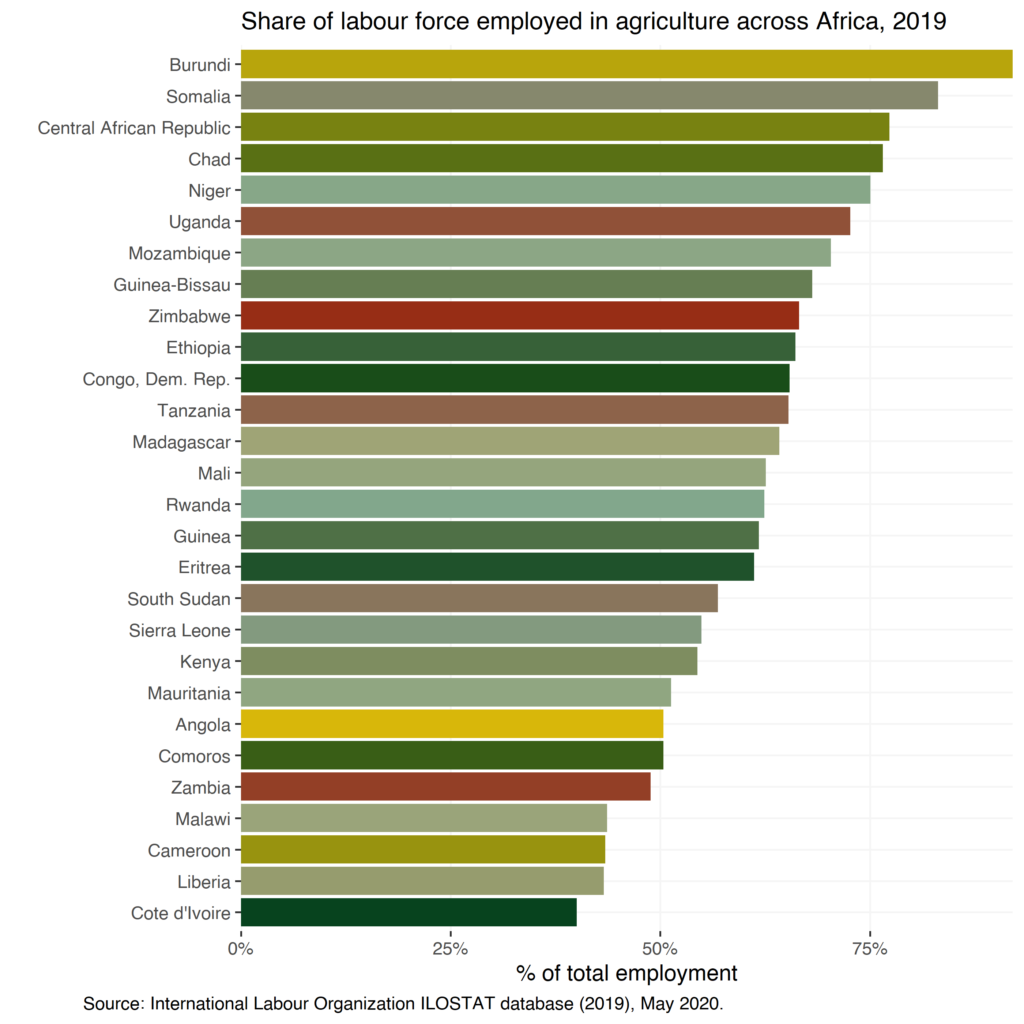

Factors that influence Africa’s vulnerability to climate change stem from its high dependence on natural resources, limited financial and institutional capacity, low GDP per capita and high levels of poverty. Employment in agriculture remains high across the continent; as of 2019 an average of 44% (of total employment) was in agriculture. The graph below provides the estimates for agricultural employment for African countries that have more than 40% of total employment in agriculture. Long-term temperature and rainfall variations will have a serious impact on the livelihoods of African citizens.

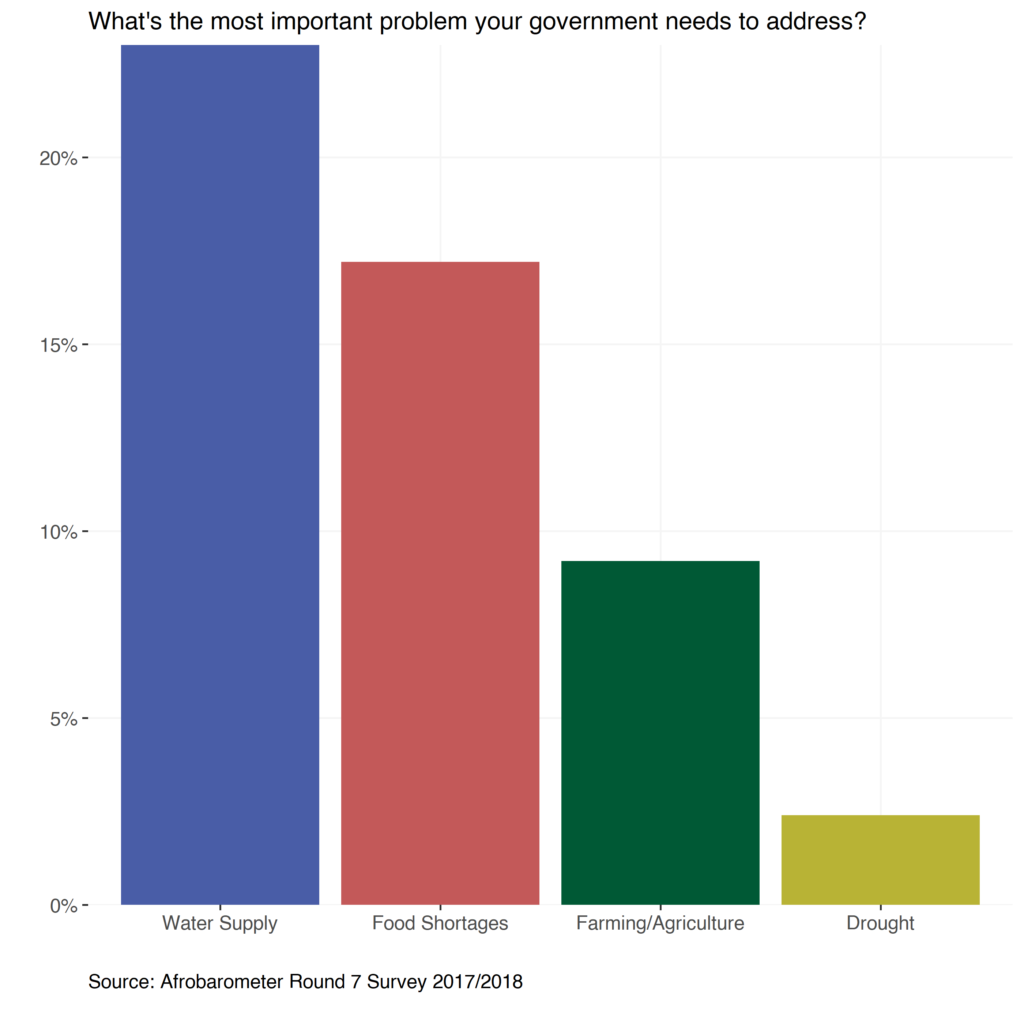

Agriculture remains an important economic activity for more than half the continent and will be a sector greatly affected by climate change. In the recent Afrobarometer Round 7 (2017- 18) Survey, “climate change” was not identified as the most important problem respondents believed their government should address, although many respondents cited water supply (23%), food shortages (17%) and agriculture (9%) as urgent issues that needed to be addressed. Those responses are embedded in the issues that climate change poses for African citizens. Climate change will certainly have an impact on any developmental progress made in these areas by African governments.

Preparing for, and adapting to, the effects of climate change will require a coordinated effort across the continent. North Africa will witness a reduction in arable land and a shortening of crop-yielding seasons due to a predicted decrease in rainfall and increase in average surface temperature. Similarly, East Africa and southern Africa are regions sensitive to climate variability and most farming practices are dependent on seasonal rainfall. West Africa’s vulnerability also relates to climate-sensitive economic activities such as livestock rearing, rain-fed agriculture, fisheries and forestry.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) predicts that, under a high-emissions scenario, land temperatures over the African continent are likely to rise faster than the global land average. National governments are well aware of the risks climate change poses for future development on the continent, but under-resourced and fragmented institutional frameworks have caused most countries on the continent to be among the least prepared to adapt to climate change, according to the Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative Index.

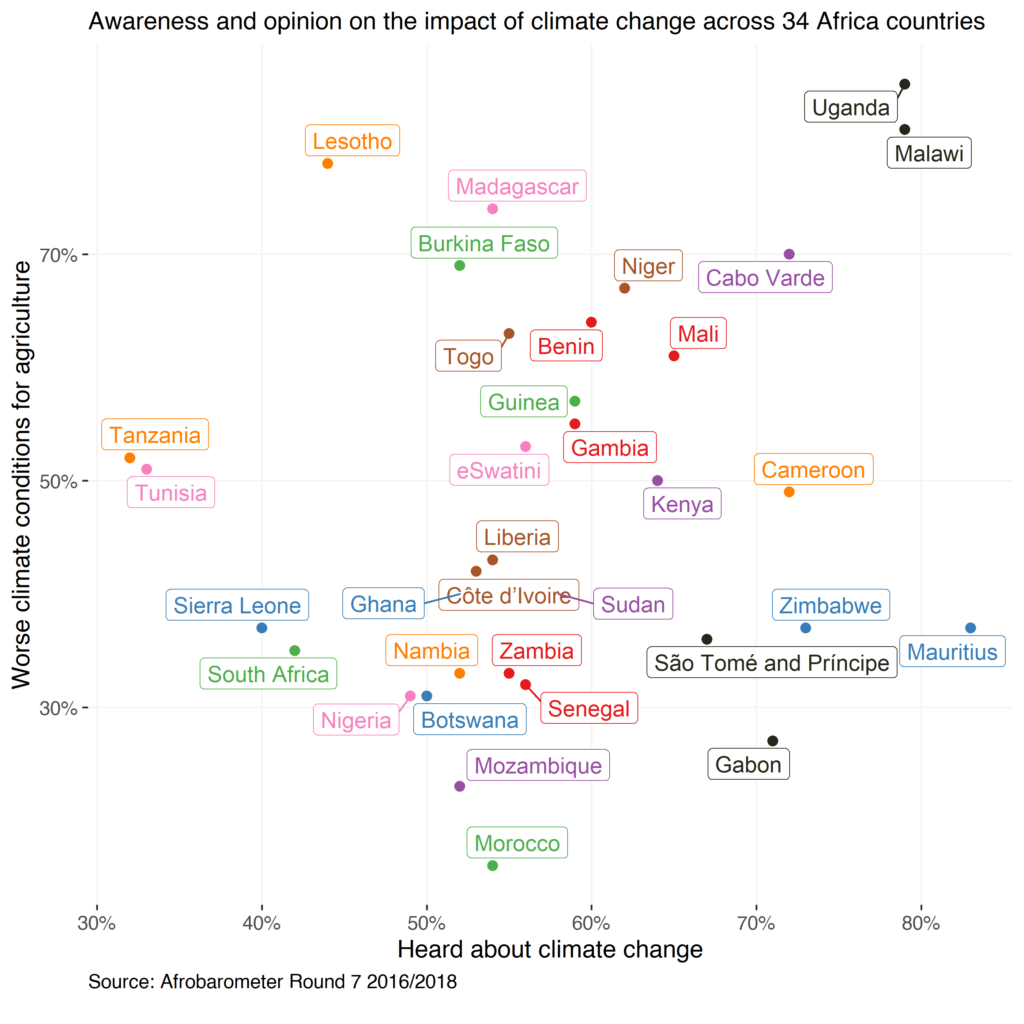

Building up resilience and capacity will require a coordinated effort by both national governments and their populations at large. Perceptions of climate change are arguably guided by national government and business rhetoric on the topic as well as by the personal experiences of ordinary citizens with regards to weather pattern variability. Afrobarometer’s Round 7 Survey conducted 45,823 interviews across 34 African countries, covering almost 80% of the continent’s population, between 2016 and 2018.

The survey included nine questions relating to climate change. The first question asked respondents to rate climate conditions compared to a decade ago; some 48% answered “worse” or “much worse”. An overwhelming majority of respondents from Uganda (85%), Malawi (81%) and Lesotho (79%) had witnessed worse weather conditions for agricultural activities. Only 23% of Mozambicans agreed that climate conditions had worsened, but this fieldwork was conducted prior to the devastating cyclones that hit the country in 2019.

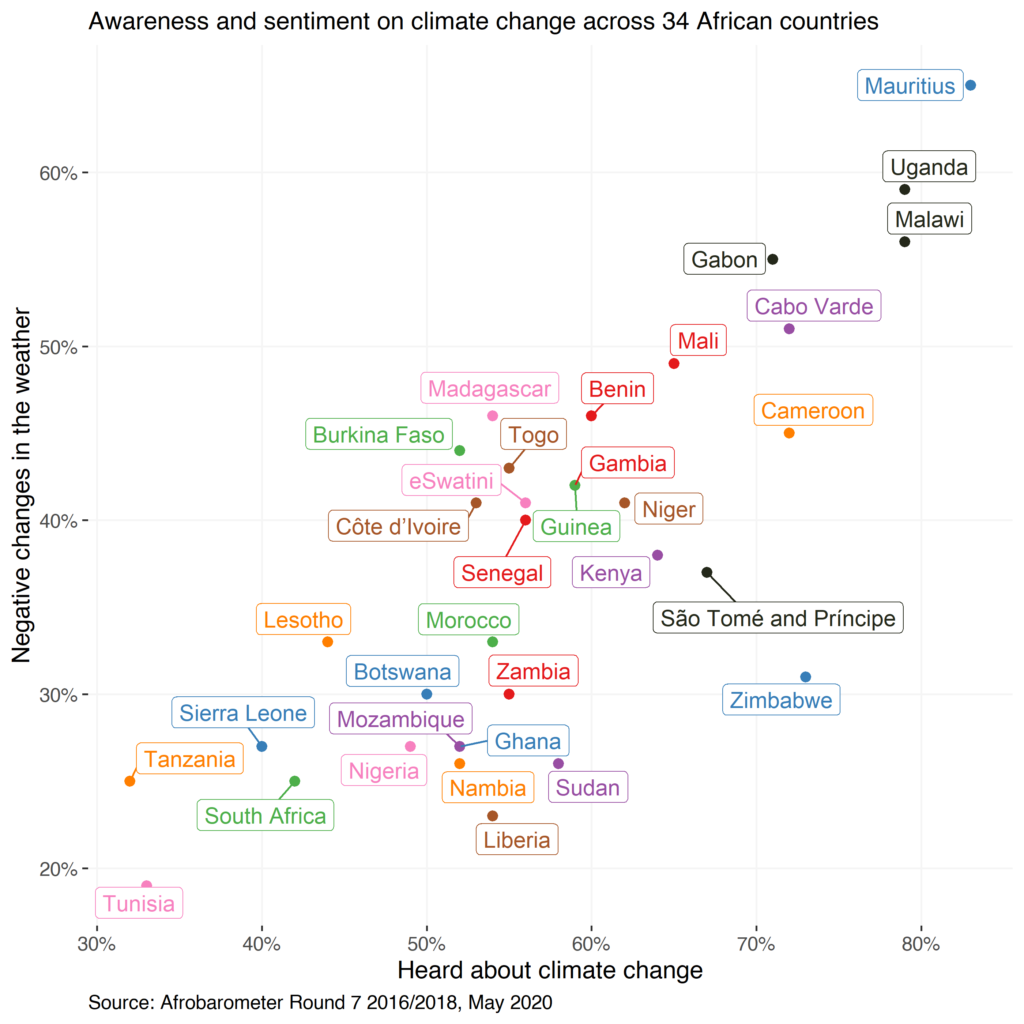

Figure 3 indicates the distribution of respondents who had heard about climate change and believed they had experienced “worse” weather conditions over the past decade. Less than half of the South African citizens had heard about climate change and even fewer believed it had made weather conditions worse. Most ordinary citizens had heard of climate change, but opinions were mixed on whether it had made weather conditions worse.

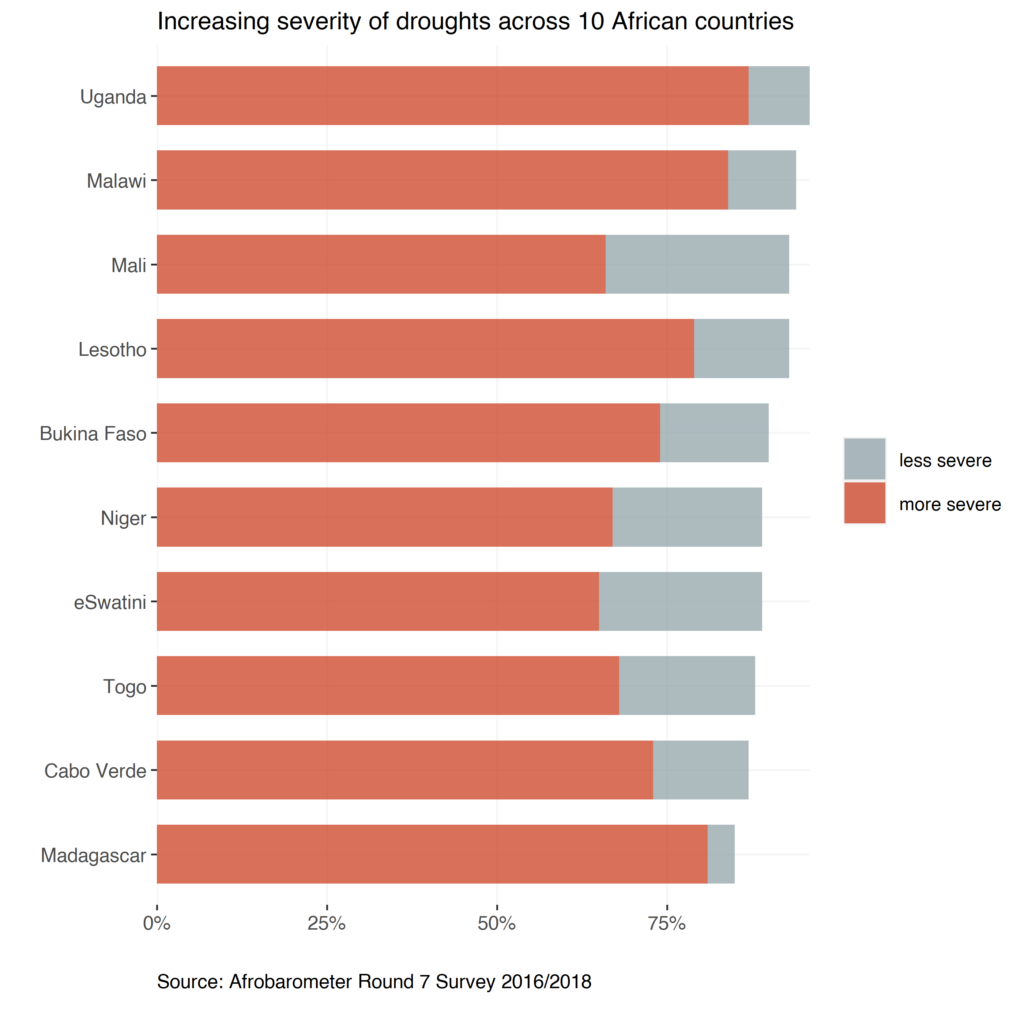

Citizens were asked to rate whether extreme weather events such as drought or flooding had become “more” or “less” severe where they lived over the past decade. Almost half the respondents reported drought as being somewhat or much more severe, while 28% thought it had become less severe. Figure 4 shows the countries where drought has worsened. In early 2017 drought hit Uganda and its impact was felt most along its so- called “cattle corridors” and into its agricultural sectors. During this period, food insecurity rose to acute levels across most of the eastern and northern parts of Uganda.

The severity of flooding was similarly seen as much worse in both Uganda (73%) and Madagascar (67%), which could be closely linked to the increase in drought intensity. When examining the demographic splits for the continent, respondents living in rural areas were more likely to observe worse weather patterns than those living in urban areas. There was a similar contrast among age groups; respondents over the age of 56 were more likely to provide a more negative view of historical weather changes than the younger age groups.

Occupation also played a role in the kind of response citizens gave: six out of 10 respondents whose occupations were in agriculture, fishing or forestry observed worse or much worse climate conditions over the past decade. Exposure to news from any source was also associated with higher levels of awareness. However, those who got their daily news from either the internet or social media sources were much more likely to have heard of climate change. Part of being informed about climate change is understanding the meaning of the concept itself. Citizens were asked whether climate change meant negative, positive or other changes in weather patterns and on average two-thirds associated it with negative changes in the weather.

Figure 5 indicates whether those who had said “yes” to hearing about climate change had in fact an understanding of its negative effects on weather patterns. Zimbabwe stands out in that although most of their respondents had heard of climate change, only 31% thought it might be an adverse phenomenon. Among the continent’s most politically influential countries such as Ghana, Nigeria and South Africa, only around one in four citizens had a basic awareness of climate change. Overall, Africa’s perceptions of climate change lack any uniform pattern and awareness remains as varied as its natural environment.

Many countries are experiencing changes in their weather patterns and evidence suggests these are having a dire impact on farmers and food security. Although nearly 60% of Africans are at least aware of climate change on average, some of the continent’s biggest players lag behind in widespread awareness and understanding. Collective awareness and an understanding of climate change by ordinary citizens will be crucial when governments try to adapt and mitigate its consequences for socio-economic development. Capacity building for early warning systems and mitigation strategies are important to assist those citizens who are most vulnerable to the effects of climate change.

Monique Bennett holds a Master’s degree in International Relations from the University of the Witwatersrand. She is currently pursuing her Doctorate in Political Science at Stellenbosch University funded by the Peace Research Institute of Oslo. She enjoys a mixed-methods approach to research across topics such as governance, environmental issues, human security and peacebuilding within the African context. She supports her research team by providing data-driven evidence for their research/op-eds and writes for various South Africa news outlets.