By Siseko Maposa & Mxolisi Zondo

South African President Cyril Ramaphosa recently announced that BRICS decided to admit Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates as permanent members.

For many, the announcement represents progress towards establishing an alternative investment vehicle competing with the hegemony of Western finance, specifically the US dollar, which has dominated the global economy over the past 80 years and is used in 80% of international trade. The promise is investment funding without conditionalities or structural adjustment initiatives and decreased economic dependence on Bretton Woods institutions and Western capital markets.

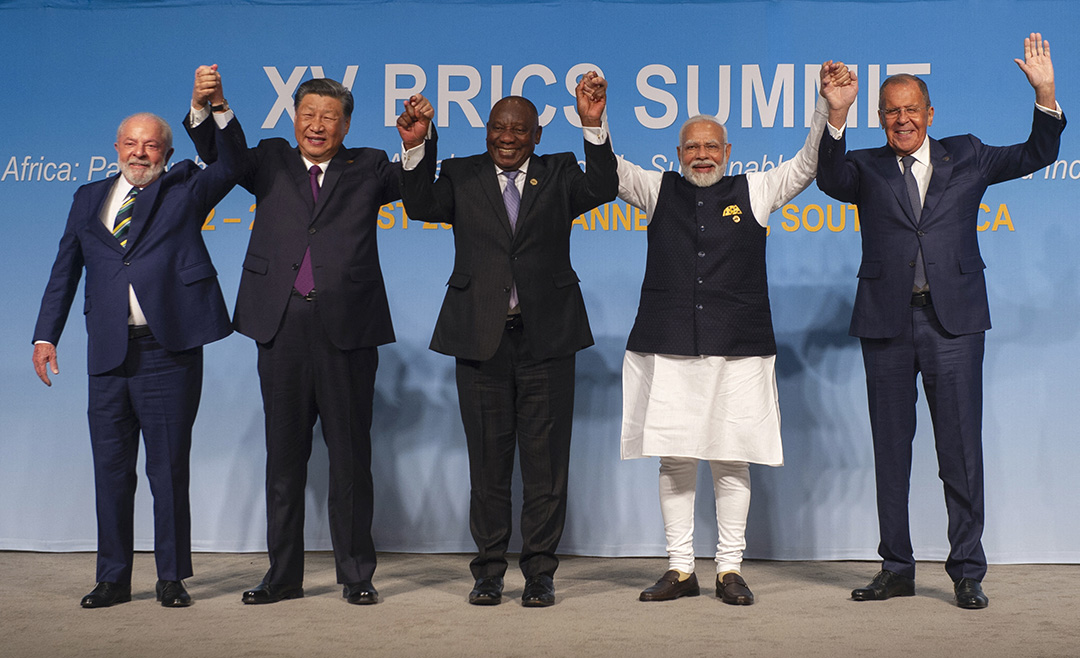

From left: Brazil’s President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, China’s President Xi Jinping, South African President Cyril Ramaphosa, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Russia’s Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov at the BRICS Summit in Johannesburg on August 23, 2023. Photo: ALET PRETORIUS/AFP

Others, however, do not see such a promising picture. They argue that irrespective of the new members, BRICS will largely remain a symbolic bloc of countries and will not emerge as a global centre of power “for remoulding international trade and finance structures.” Critics further argue that because of the vast political and economic differences between member states, BRICS will stumble in its attempts to produce a consolidated programme of action.

Where both opposing views find some commonality is that the success or failure of BRICS will largely, if not entirely, depend on the ability of member states to positively identify common political and economic values, catalyst investment pathways, and the creation of an equitable benefit-sharing regime. A successful BRICS will also need key components of effective multilateral institutionalism, including effective communication and consensus-building, clear and enforceable institutional frameworks, and financial stability.

BRICS’ current agenda may likely exclusively focus on guaranteeing that member states adhere to the governance policies, rules, and norms and ensuring that member states participate effectively within the institution. In addition, the bloc will need to speedily identify common shared interests to create institutional consensus and rally consorted efforts –not on strong anti-western sentiments but on casting a positive vision for a global future. For the time being, this is likely through increased cooperation in producing the ingredients for economic growth within each country – this includes ensuring the affordable supply of energy, infrastructural development, technological advancements, and skills capacitation.

The building work that BRICS must commence will also be difficult because of the many obstacles the institution must overcome.

At who’s cost and for who’s benefit?

Multilateral organisations require consistency, steady funding, and resource allocation to implement objectives successfully. This requires tremendous financial stability and commitment from member states. Currently, China, the world’s second-largest economy, is bearing the cost burden – but this does not come without its own difficulties. There is the threat that China may hold vested interests in maintaining the organisation to extend its influence and global agenda (the realist perspective). Already there are tensions between China and India concerning border disputes. Russia also articulates itself as a strong power within the global system and will most likely contest any efforts by China to dictate the political and economic programme of BRICS. Simply put, Chinese dominance of BRICS may be a central contention threatening the core of the bloc’s agenda.

China faces grave economic woes, characterised by slow, if not stalled economic activity and a worsening foreign investment and property crisis. China’s property crisis emerged in 2020 following President Xi Jinping’s crack-down policies, which imposed more than 100 regulations on property businesses that raised huge money via equity funds, borrowings, and IPOs. In attempts to manage a property bubble, Jinping’s policies set in motion a massive debt crisis within the property market in 2021, which led to companies accounting for 40% of Chinese home sales, most of them private property developers, to default.

The property crisis has created a context of massive debt, with short-term growth that has not translated into fixed capital that can sustain growth. China’s flagship technological sector also faces astute challenges. Late last year, Washington took an unprecedented decision to stop exporting certain semiconductor chips and chip-making equipment to China. The move is designed to contain China’s tech ambitions as these technologies are used across many sectors, including advanced computing and manufacturing. Times magazine reported that “global investors have pulled more than $10 billion from China’s stock markets, with most of the selling in blue chips”.

The political and economic woes China faces may threaten its ability to fund BRICS operations. In order to incubate the organisation from this, it will be essential that all member states contribute sufficiently to the BRICS programme – but given that many of the states exhibit economic difficulties (high debt rates being at the forefront), funding BRICS will remain challenging.

In addition, who benefits from BRICS will remain an important question. The literature is rather clear on this – member states are more likely to actively participate and contribute to multilateral organisations when they perceive a fair distribution of benefits. Suppose an equitable benefit-sharing regime is not created. In that case, we may see increased factionalism within BRICS, with forefront states on one end and back-bencher states on the other end of the spectrum. This will have a limiting effect on the institution’s efforts.

Currency! But how?

Since a senior Russian official stated this year that BRICS was embarking on establishing a BRICS currency, the international community has watched developments closely. The de-dollarisation campaign, however, has taken a few blows along the way, with member states seemingly showing little to no interest in the cause. This may be attributed to the fact that the US dollar remains the currency of international trade, and member states’ economies remain intricately tied through export and exchange rates on the dollar. At the BRICS Summit, little to no consensus was found on the creation of a BRICS currency which may indicate that for the time being, this will remain a huge bone of contention for BRICS member states.

There are also several hindrances that stand in the way. Creating a BRICS currency to offset the US dollar will require uniform standards and principles amongst member countries. In addition, the currency will need to find some stabilising instrument to protect it from volatility and be useful for international trade.

A much more feasible path for the time being would see BRICS increasingly trade more in local currencies – to this end, some positive moves have been made by the Bloc. Most recently, the Shanghai-based New Development Bank (NDB), formed by BRICS countries in 2014, the NDB has backed the initiative by its founding members to promote the use of local currencies to ease trade and transactions. The bank intends to see a 30% rise in local currency financing by 2063. The bank expects to lend up to $10 billion this year to member states – 30% being local currency borrowing.

The BRICS bank has also recently conducted its first sale of bonds denominated in South African rand as emerging markets seek greater access to local currency funding. The bonds, which have a R1 billion five-year note and R500 million three-year note, attracted R2.67 billion in auction bids. Combined, these moves may aid in reducing the dependence of member countries on Western markets, which are often seen as volatile.

It may really go either way

It will be interesting to see if BRICS can navigate through these obstacles. The institution will need to exert much effort in consensus building. If it can do this efficiently, effectively, and with good dexterity within the next 50 years, we may witness BRICS emerge as a new centre of power, offsetting US global dominance.

However, it is important to note that while there are many doomsayers, we should not forget that many Western countries and BRICS members have shared interests. As such, and in agreement with Research Professor on Peace, Conflict, and Development at the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs, Dr Cedric H de Coning, “While it is prudent to be cautious, it may also be wise to explore cooperation in those areas where there are shared interests rather than assume that the BRICS and the West are strategic rivals on all fronts.”

- Siseko Maposa is the Director for Surgetower Associates, a foreign affairs consultancy.