Three decades ago, China (like many developing countries of the time) barely had any tech industry to speak of, remaining largely dependent on foreign companies to supply its technological and communications infrastructure needs. Since then, however, the Chinese state and society have both made great leaps in becoming a major technology innovator, supplier, and operator.

The country has ambitious plans to dominate technology manufacturing by 2025 and to take the lead in standard-setting by 2035. In its efforts to achieve these lofty goals, and under the banner of the Digital Silk Road (DSR), the Chinese government is rallying both private and state-owned companies to develop digital infrastructure at home, export more sophisticated tech products abroad, and augment the compatibility between Chinese and foreign networks.

Officially unveiled in 2015, very little is known about the DSR, a component of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) – a massive transcontinental infrastructure connectivity project. In typical Chinese Communist Party (CCP)-esque fashion, the Chinese government has not provided any clear mandate or outline concerning the makeup of the DSR, making it challenging for outsiders to determine its configuration and purpose. However, in trying to make sense of the initiative, it can be somewhat understood as an effort by the state to expand its digital footprint globally and to further its ascendance as a technological power.

Through the DSR, China seemingly seeks to refine its technological skills and offerings, thereby positioning Chinese technology at the centre of global networks, prioritising next-generation technology and next-generation markets. The primary purpose of the DSR is to ensure that leading Chinese technology companies – such as Alibaba, Tencent, Baidu, and Huawei – and state-owned telecom firms – such as China Mobile, China Telecom, and China Unicom – can take advantage of the political and financial support that Beijing is investing in the DSR project to create market access for its tech giants, enabling their ability to compete in emerging markets with foreign (but mostly the US) technology firms.

Although many Chinese digital infrastructure and ICT projects around the world predate the DSR, most are now being branded as part of the initiative so that these companies can reap political and financial support from Beijing. Due to the opaque nature of Chinese foreign investment, it is difficult to determine the exact scale of China’s tech investments. Nonetheless, research undertaken by the International Institute of Strategic Studies (IISS) estimates that China is engaged in 80 telecommunication projects globally and, according to the RWR Advisory Group, has invested approximately $79 billion in DSR projects worldwide.

Shanghai skyline at night. Photo: Getty Images

As China’s digital presence expands globally – and especially against the backdrop of tech tensions between China and the West – the Chinese have become increasingly concerned with promoting digital sovereignty, commonly referred to as cyber sovereignty. Digital sovereignty can be simply defined as the capacity of a state to regulate and have control over technology in use and includes data, hardware, and software. Digital sovereignty has become a growing concern for countries wishing to reduce their dependence on a handful of established tech power brokers – mainly the US, which houses most of the world’s data and tech companies with outsized power and sway.

Essentially, the digital climate is changing. According to Ciaran Martin, of the Blavatnik School of Government, the geopolitics of technology has for years been orchestrated by a “technological ecosystem built by the US’s private sector.” China’s technological ambitions are not “to compete on the American-built, free, Open Internet” system which is informed by liberal democratic values, but to construct an entirely new, more state-controlled – some would say authoritarian – model that is forcing the bifurcation of the internet where market participants and countries will have to choose between the US and China.

In response to China’s expanding cyberspace capabilities (and to curb its digital influence and power), the US State Department launched the “Clean Network” initiative in August 2020; it aims to remove Chinese digital companies from the global supply chain by recruiting countries and companies to adhere to a set of shared principles in technology standards and practices. Mike Pompeo, the US’s former Secretary of State, announced in November 2020 that 53 countries had signed on to the initiative.

In a counter-response, the Chinese Foreign Ministry introduced the “Global Data Security Initiative (GDSI)” in September 2020, which aims to enhance global cybersecurity by focusing on data storage and digital commerce security. As pointed out by DigiChina, a research centre based at Stanford University, the GDSI seeks to dispel the US’s portrayal of Chinese technology as “malign and untrustworthy” and a threat that needs to be excluded from the global internet infrastructure. To date, quite a few countries have expressed support for this initiative, including Russia, Tanzania, Pakistan, Ecuador, the Arab League nations, and ASEAN countries.

To exert absolute digital sovereignty, countries need to have their own data centres to ensure that all government and personal data is stored within the country, and that this digital data is subject to national laws. To this end, China has undertaken mega data centre projects to boost its own data storage capacity. Beyond mainland China, Chinese tech companies (such as Huawei and Tencent) are building data centres for countries mostly located in the Global South.

China’s interest in Africa’s ICT sector dates to the late 1990s, when both its private and state-owned companies tentatively began entering African markets. China’s involvement in developing Africa’s ICT infrastructure coincided with the continent’s telecom revolution of the 1990s when African countries were liberalising their telecommunications sectors and looking to upgrade their infrastructure.

Consumers and businesses are rapidly embracing the use of technology to enhance or automate financial services and processes. Photo: Getty Images

In Africa, Chinese firms such as Huawei, ZTE, Cloudwalk, and China Telecom have been key in building and upgrading digital infrastructure. Data compiled by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute shows that China has “built 266 technology projects in Africa, ranging from 4G and 5G telecommunications networks to data centres, smart city projects that modernise urban centres, and education programmes.”

As a result, “Made in China” technology is now the backbone of network infrastructure across many African countries. Without much competition from foreign (and especially western) companies, the Chinese have been able to entrench themselves in Africa’s ICT sector, effectively positioning themselves as the providers of next-generation technology for the region. Through the DSR, Chinese firms operating in Africa’s tech sector can expand and enjoy the fruits of scaling up their operations.

The political and financial support that Beijing provides for DSR projects “enables Chinese enterprises to not only meet… the digital infrastructure needs of African countries, but also their financing needs, enabling Chinese firms to pursue their corporate interests, African countries to meet their needs for infrastructure and associated financing, and the Chinese state to achieve its strategic goal of strengthening its engagement in the region while advancing its [rise as a technological power].”

Only a few big US multinational technology companies – Google, Microsoft, Amazon, and Facebook, have a presence in Africa. Western IT infrastructure companies cannot compete with their Chinese counterparts without political and financial backing from their neoliberal-economic-adhering governments. Without government support, western companies are reluctant to enter African markets. This is because many western companies do not have the appetite to invest in African countries with challenging and risky business environments.

With African countries desperate for digital infrastructure to transform their economies, their governments continue to work with Chinese technology firms. With other foreign companies reluctant to take on big projects needed to develop critical ICT infrastructure, African countries are left with little choice but to partner with the Chinese. The availability of financing from Chinese banks and the competitive pricing of high-quality products offered by Chinese companies makes it advantageous for African governments to partner with Chinese technology companies because “for Africa, Chinese-built internet is better than no internet at all”.

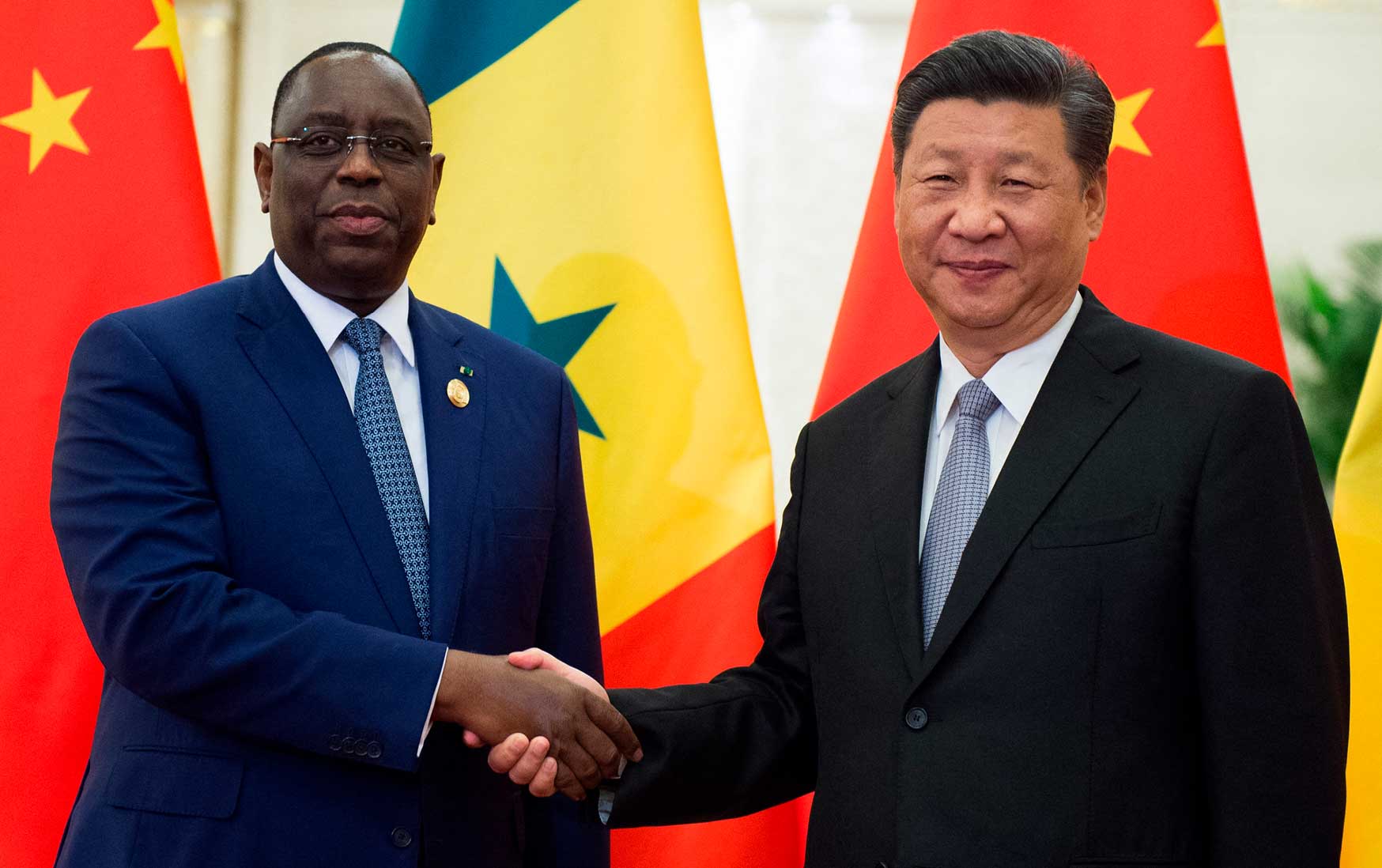

Senegal’s President Macky Sall shakes hands with China’s President Xi Jinping before their bilateral meeting at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing in September 2018. Photo: Nicolas ASFOURI / POOL / AFP

To keep pace with Africa’s social and economic transformation – which is exerting considerable pressure on existing digital infrastructure – it is estimated that 1,000 MW capacity and 700 new data centres will be needed. Chinese companies, such as Huawei, have already begun to deliver multimillion-dollar data centres and cloud services in several African countries, including Zimbabwe, Zambia, Togo, Tanzania, Mozambique, Mali, and Madagascar. Huawei’s national data centre project in Senegal, commissioned in June 2021, is particularly special given that it is explicitly linked to the aim of “guaranteeing Senegalese digital sovereignty”. Senegal is the first African country to partner with China in moving all its government data and digital platforms from foreign servers to a new $79 million national data centre financed by the China Export-Import Bank.

In light of tech tensions between China and the West, many analysts and leaders – and especially those in western policy circles – are concerned about how involved China has become in Africa’s tech sector. Because many Chinese ICT companies have ties to their government, it is feared that Chinese-built digital infrastructure projects, such as data centres, can be leveraged by China to spy on national governments and covertly gather intelligence.

Given reports that China had spied on servers at the African Union for more than five years, gaining access to confidential information, concerns over the country’s dominance in Africa’s ICT sector are not unfounded. However, the revelations of Edward Snowden on the US National Security Agency, which accrued vast amounts of information via ICTs, shows that the US is just as capable of using ICT infrastructure for covert purposes.

So, with the Chinese and Americans equally capable of using their technology for secret intelligence gathering, which country should African countries partner with to build their ICT infrastructure? Unlike the US, which subscribes to a “free and open internet” policy, the risk with the Chinese is that they could influence African countries (especially those with more dubious regimes) to adopt a digital authoritarian model of internet governance (as in China). This form of digital governance is the antithesis of the digital democracy principles that the US promotes.

Looking at the bigger picture, we need to think beyond the tech competition between China and the US in Africa and more about how the technology (provided by either of the two) will be used and governed. Regardless of which foreign companies are involved in developing the continent’s digital infrastructure, it is up to African policymakers and governments to safeguard their digital sovereignty and develop their own digital governance models. There is also a need to be both pragmatic and cautious, monitoring the amount of foreign involvement in the continent’s technology sectors, irrespective of whether it is western or Chinese.

[activecampaign form=1]

Dr Mandira Bagwandeen is a senior research fellow at the Nelson Mandela School of Public Governance at the University of Cape Town (UCT), where she focuses on Africa's regional integration and industrialisation and Africa-China relations. She also lectures international relations courses at UCT's Political Studies Department. Mandira is affiliated with several think tanks. Mandira has produced commentary and written several articles on Africa-China issues for various local and international media outlets.