Cameroon: culture clash

Urbanisation and acculturation in Cameroon are eroding traditional conservation practices that helped maintain the equilibrium of the ecosystem

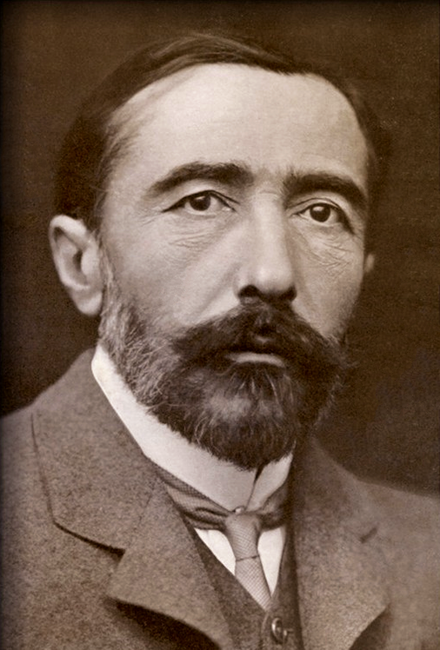

Aerial view of the Mount Cameroon National Park in the south west region of Cameroon, 2019. The forest at the foot of the mountain plays host to African elephants traditionally conserved by the Bakweri people but are now under threat Photo: Muleng Timngum

Armand Boui has a problem. The 57-year-old native of Mongonam in the Kadey Division of Cameroon – part of the species-rich Congo Basin – is jobless. He wasn’t always unemployed, and he is not at peace with himself. Boui is an herbalist and intercessor between the community’s people and their ancestors. But about 10 years ago, he watched helplessly as wildlife poaching and a gold rush led to the desecration of a sacred forest – the source of his spiritual powers. “The forest was invaded by strangers, and even our own [people]. The traditional authorities of the village couldn’t help.

Subsequently, my potions and incarnations gradually became ineffective,” Boui said. People stopped patronising him and, suddenly, he was left without his social role – or a job. “The spirits were no longer finding favour in me. I guess they moved away due to the invasion. It is an unfortunate situation,” Boui told Africa in Fact. He sometimes wonders what his late father would think. His father, from whom he inherited the therapeutic and sacral role, had asked him to hand over the “special gift” to the next generation.

In Cameroon, many natural sites and biodiversity hotspots play host to totems, especially in the form of animals, which are revered for their traditional sacredness. The totem animals, such as elephants, gorillas and chimpanzees, were formerly protected by traditional belief systems, but are now endangered species. In recent times a cocktail of factors, including acculturation and rapid urbanisation, has disrupted traditional conservation practices that helped maintain the equilibrium of the ecosystem.

Boui’s predicament is not unique. Studies carried out in different parts of Cameroon show that fast-eroding cultural norms and taboos are playing negatively against wildlife conservation. Fewer than 10 Bakweri (people of the Sawa ethnic group who speak the Mokpwe language) villages out of about 100 located near the Mount Cameroon National Park still have functional secret societies, according to a 2004 report by researcher Lyombe Eko. In general, the aim of traditional secret societies is to safeguard their communities from evil.

The secret societies he identified as still active in these villages were the Maale, whose totem is the African elephant, and the Nganya, with the warthog as their totem. Members of both groups claimed that their respective totem animals were present in the forest; they were protected and could not be killed for merely economic reasons. These traditional belief systems played an important role in wildlife conservation in the past, according to Chief Dr Ndome Samuel, traditional ruler of Kake II Bokoko in the South West region of Cameroon, in a pronouncement.

But European missionaries – including Baptists, Catholics and Presbyterians – dissuaded the locals from the practices, promising hell for adherents who didn’t repent. Many abandoned the culture. Religion and colonisation – related factors of acculturation – have had a devastating impact on traditional ecological governance systems, says Nnah Ndobe Samuel, a Yaounde-based socio- economist. He argues that irreversible damage to Cameroon’s rich and abundant ecosystems, related biodiversity, cultures and traditions could occur if their influence is not checked.

Skinned porcupines at a local game market in Bertoua, 2016. Photo: Amindeh Blaise Atabong

“Approaches by corporate conservation organisations such as the World Wide Fund for Nature, Wildlife Conservation Society, the Zoological Society of London, the African Wildlife Foundation, etc, are too scientific and colonial. They do not take into consideration the specificities of local people,” Ndobe told Africa in Fact. He noted that most of their approach often results in a hunting market, to the advantage of hunters from the West.

Colonialism turned many things upside down, according to Ndobe. Its influence touched everything. French colonialists in Cameroon, for example, forced traditional rulers to wear uniforms, abandoning their rainforest design attire and amulets. Urbanisation has also taken its toll on traditional best practices related to conservation. Cameroon has an urbanisation rate of 56% per cent, according to United Nations (UN) data; making it one of the most urbanised countries on the continent by sub- Saharan standards.

In absolute terms, more than half of the country’s 25 million people now live in urban areas, with the UN forecasting 70% by 2050. This rising rate of urbanisation involves significant challenges for humans. But the future for animals is bleak. As pressure increases on land for construction, agriculture and other economics activities, their natural habitats are destroyed. Also, over the years, state legislation intended to protect and manage wildlife has often failed to recognise and provide for local communities.

These influences are difficult to counter, says Ndobe, who does much of his work in the Kupe Muanenguba area. As an example, he cites the efforts of the Baka pygmies in the east of Cameroon to resist acculturation through voluntary isolation. “The modern conservation system doesn’t consider them. [The] pygmies are chased out of their natural habitats when government creates reserves or grants logging concessions,” Ndobe says. About 20 years ago, the government started granting logging concessions to mostly Chinese and European companies.

Many of Cameroon’s 75,000 hunter-gatherer pygmies were forced to leave the forests and found themselves living sedentary lifestyles by roadsides. The Baka pygmies in particular have protested against their eviction from ancestral forests, where they traditionally harvested wild fruits and hunted game for subsistence. Their survival, and the destruction of their culture, are at stake. In 2017, Survival International, a group campaigning for the rights of indigenous people, accused the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) of violating international guidelines in Cameroon by backing the creation of three national parks on Baka land without their consent.

The group said that the WWF had funded eco-guards who allegedly tortured and killed Baka pygmies with impunity in anti-poaching operations. The WWF, which has its headquarters in Switzerland, has denied the accusations, but the Swiss government has said it will look into the issue. Experts highlight other factors that hamper the survival of traditional conservation systems. These include paradigm shifts in lifestyles and attitudes, poor transmission of cultural knowledge to younger generations, the decline of traditional institutions and the rise of individualism, among others.

Dead pythons on display at a local game market in Bertoua, 2016. The snakes are harvested from protected areas across the forest east region of Cameroon, part of the species-rich Congo Basin Photo: Amindeh Blaise Atabong

Yet experts and civil society activists agree that integrating cultural norms and taboo – which are rooted in traditional belief systems – into forestry and wildlife laws and conservation programmes could help to galvanise locals into conserving natural resources, thereby contributing to resourceful nation building. With regard to conservation, traditional belief systems ought to be incorporated into law enforcement mechanisms, they say.

“If this is done, it will encourage the spirit of stakeholders (local people), recognise and promote a sense of ownership and belonging,” says Dr Nkwatoh A Fuashi, Senior Environment and Natural Management Adviser for the Environment and Community Development Association (ECoDAs) and a lecturer in the Department of Environmental Science, University of Buea, an advocate of incorporating traditional belief systems in conservation laws in Africa. “This has been neglected by the international conventions that are the genesis of our present national laws on the conservation of resources.”

This may be particularly true of the Congo Basin, where some traditional practices do survive. In Nigeria’s Gashaka-Gunti National Park, primates are “naturally protected”, Fuashi says, because members of the local community view them as part of the human species, so that killing them would be similar to killing a human. Practices such as this should be incorporated into conservation mechanisms, he argues.

Though efforts have previously been made to get local communities involved in conservation programmes, they have largely been informed by economic motives, frequently under outsider direction. Moreover, Asian demand for certain species, such as pangolins and rhinoceros, facilitated by widespread corruption, has fuelled poaching. Communities take steps to prevent such species extinctions when they attach cultural significance to them, according to Dr Marius Talla, an expert in governance and anti-corruption at consultancy firm Cabinet Mamy Raboana.

“If [wildlife extinction] happened, their customs, and therefore their lives, would be over. We saw it with the pygmies of east Cameroon,” Talla says. Talla believes there will be better conservation results if traditional conservation best practices are made law and there is effective reduction of corruption in the chain of suppression of wildlife offences. “All other measures will only be complementary,” he says.

In 2015, custodians of traditions from six African countries, including Cameroon, jointly petitioned the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights to give legal recognition to sacred natural sites and territories and their associated customary governance systems. In their joint statement, they asked the Commission to encourage member countries to observe the ideals of its charter – “giving precedence to indigenous African culture and customary governance systems over the colonial systems that dominated the continent for so long.”

In practice, however, these processes must be negotiated at regional and country levels, and can therefore take a long time, says Ndobe. Hope, and continued advocacy of the approach, are essential.

Amindeh Blaise Atabong is a Cameroonian freelance journalist. His interests include gender, human rights, climate change, environment, tech, conflict, peace-building and global development. In 2019, he was a finalist in the inaugural True Story Award, and also won a prestigious Kurt Schork Award in International Journalism. His works have been published by independent regional and international outlets, including Quartz, Mail & Guardian, Reuters, Jeune Afrique, Epoch Times, African Arguments and Equal Times.